Bill Hawthorne is an Ulsterman now living in Kingswear.

Today’s 100th anniversary of the first day of the Battle of the Somme is particularly poignant for him as both his father and future father-in-law went ‘over the top’ in the bloodiest battle in military history.

Dr Hawthorne was formerly a university lecturer in mathematics and mathematics education, an award-winning documentary film director, an Open University tutor, a British Council officer and a senior research Fellow at the University of Ibadan.

He is the author of numerous school textbooks on mathematics. He has been fully involved in encryption technology since 1986. His work in this field is published in seven languages.

He says he ‘enjoys music and the arts, boating, teaching mackerel to be more careful in future and learning from the vast experience of his contemporaries’.

In his own words. he writes this moving tribute...

FRIDAY, July 1, 2016, is the 100th anniversary of the morning when my father, Private Thomas Hawthorne, and my future father-in-law, Second Lieutenant Hamilton Donaldson went over the top in the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Both were members of the Ulster Division.

My father was a stretcher bearer and a front-line assistant nurse and I can hardly imagine how he suffered on that first day.

The General Staff had mistakenly believed that the preceding barrage would wipe out the German defences, so it was only a matter of walking over the ripped barbed wire with a full 60lb pack.

But what really happened was that the minute the soldiers went over the top they were raked with machine gun fire from German infantry who had, unknown to the British General Staff, been hiding 40 feet deep and safe from the British bombardment.

Over the next two days, the Ulster Division lost some 5,500 killed, wounded or missing and, of these, around 2,500 had been killed. Most of the Ulster Division had been members of the Ulster Volunteer Force, so you can imagine the devastating effect on Ulster villages.

My father’s job was to make instant decisions as to which of two mutilated bodies had the better chance of survival when carried back to the field hospital. During the night he held wounds open while surgeons looked for shrapnel and hidden bullets.

Second Lieutenant Donaldson had a different role. We have accurate family records that he was accepted as a volunteer a few weeks before his 16th birthday. He gained his commission – not because he had gone to a public school – but because he was an expert horseman. On that fateful day, he strode across no man’s land armed with a pistol, never thinking he would still be alive and unwounded by the end of the day.

Later in the war the unexpected happened to both men. Second Lieutenant (now full lieutenant) Donaldson found himself surrounded along with his platoon with not a single round of ammunition and was taken prisoner. My father contracted typhoid and spent 18 months in Addington Palace War Hospital before being invalided out.

All during my childhood I listened to my father talking incessantly about the war. No horror stories, only trivia. Then, as a 17-year-old student, I acquired an anthology of Siegfried Sassoon’s war poetry and began to piece together the realities of my father’s past.

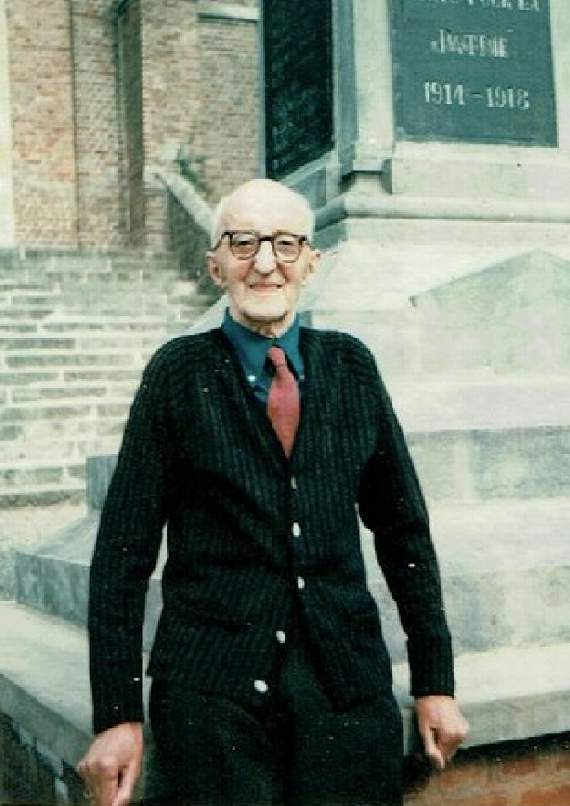

In October 1979, when I returned from British Council service in Nigeria, I found myself living near Seaford where my father did his final training before becoming the first private soldier of the Ulster Division to land in France. I invited him over to England, took him all round his training ground and then shipped him to France, following the route he took in 1915. First stop was a café cognac in Le Treport. Suddenly the silence was penetrated by the arrival of around 50 road-racing cyclists. My father was a former velodrome racer. What a perfect start. We stayed for two weeks at a hotel in Doullens from where he was able to visit his old haunts.

My standard opening was: ‘Ce mon père. Il état un soldat pendant la guerre de quatorze’.

Looking at wartime graves was harrowing. What moved me was when he met an occasional French veteran. They hugged and hugged and spoke to one another in Franglais. But what moved me even more was that, on return to Ireland my brothers told me that he never mentioned the war again until his death some eight months later. So the visit to France was cathartic but 20 years too late. I’ll never forgive myself for my stupidity.

My father-in-law’s post-war life was different. In 1966, in company with other veterans, he returned to France and actually stood on the spot from which the German machine gunners mowed down his friends and comrades.

But what hurt him all his life was the fact that when he was a POW, British dockers had refused to ship Red Cross parcels to him as a punishment for allowing himself to be taken prisoner.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.